Revisiting An Early IQuant Post

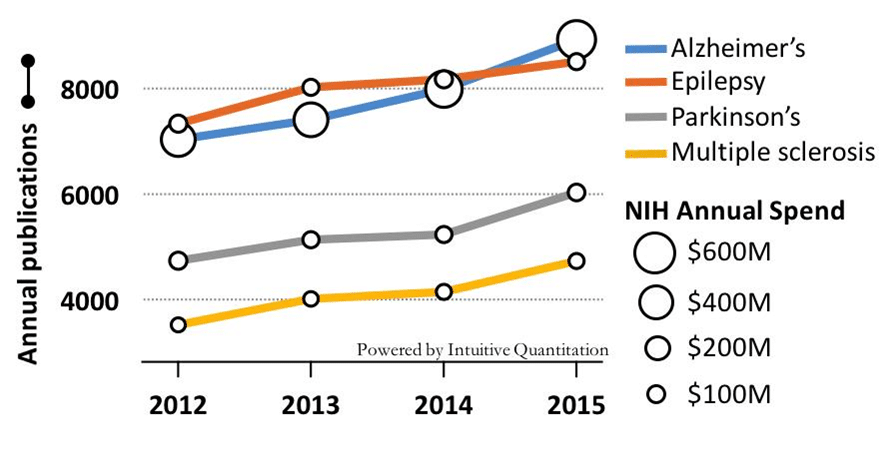

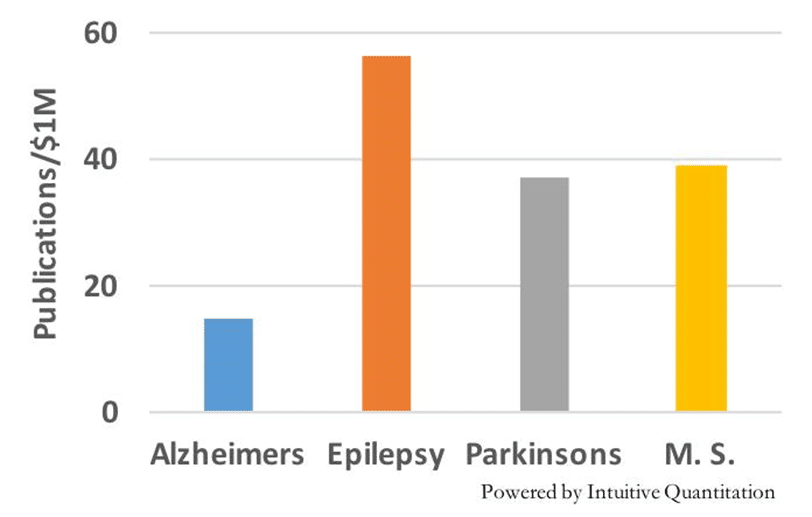

Some may remember these two charts, which I posted on LinkedIn in 2016. They highlight the disconnect between the amount of NIH grant funding for and the publication productivity for selected neurological diseases. Not surprisingly, Alzheimer’s disease won the grant funding category, but this money generated significantly fewer publications per dollar compared to other disease areas such as epilepsy, Parkinson’s Disease, and multiple sclerosis.

Figure 1 – Publications and NIH grants, 2012 – 2015

Figure 2 – Publications generated per $1 million in grant funding

During the subsequent seven years, what have these investments yielded for patients in each of these disease areas?

Notes

1. All clinical trials, (ClinicalTrials.gov)

2. All publications (Pubmed)

3. List of Annual Innovative Drug Approvals (US FDA)

4. Includes the approval of Deep Brain Stimulation

Of course, grant funding generates a variety of patient benefits, but let’s face it, new treatments are clearly the most visible and impactful.

The controversial approvals of both highly similar AD drugs raised many questions. The clinical benefit seems modest at best, each has notable side effects, and they command a premium price. Moreover, the nearly $1 billion of annual NIH grant support is only a small fraction of the total research investment in AD, which includes an uncomfortably large number of very expensive, failed clinical trials. Why has so much money has been funneled into AD research for such limited benefit? Clearly the heavy focus on a single disease mechanism, A-beta/amyloid likely squeezed out more attractive alternatives and impeded overall progress. It is certainly worth exploring, as we must learn to avoid these traps. In any case, a look into the status and prospects of alternative mechanisms is warranted. Stay tuned for more on this from Iquant.

Some may remember these two charts, which I posted on LinkedIn in 2016. They highlight the disconnect between the amount of NIH grant funding for and the publication productivity for selected neurological diseases. Not surprisingly, Alzheimer’s disease won the grant funding category, but this money generated significantly fewer publications per dollar compared to other disease areas such as epilepsy, Parkinson’s Disease, and multiple sclerosis.

Figure 1 – Publications and NIH grants, 2012 – 2015

Figure 2 – Publications generated per $1 million in grant funding

During the subsequent seven years, what have these investments yielded for patients in each of these disease areas?

Notes

1. All clinical trials, (ClinicalTrials.gov)

2. All publications (Pubmed)

3. List of Annual Innovative Drug Approvals (US FDA)

4. Includes the approval of Deep Brain Stimulation

Of course, grant funding generates a variety of patient benefits, but let’s face it, new treatments are clearly the most visible and impactful.

The controversial approvals of both highly similar AD drugs raised many questions. The clinical benefit seems modest at best, each has notable side effects, and they command a premium price. Moreover, the nearly $1 billion of annual NIH grant support is only a small fraction of the total research investment in AD, which includes an uncomfortably large number of very expensive, failed clinical trials. Why has so much money has been funneled into AD research for such limited benefit? Clearly the heavy focus on a single disease mechanism, A-beta/amyloid likely squeezed out more attractive alternatives and impeded overall progress. It is certainly worth exploring, as we must learn to avoid these traps. In any case, a look into the status and prospects of alternative mechanisms is warranted. Stay tuned for more on this from Iquant.

Let us know how we can help enhance your research.

We work with scientists, drug discovery professionals, pharmaceutical companies and researchers to create custom reports and precision analytics to fit your project's needs – with more transparency, on tighter timelines, and prices that make sense.

Revisiting An Early IQuant Post

Some may remember these two charts, which I posted on LinkedIn in 2016. They highlight the disconnect between the amount of NIH grant funding for and the publication productivity for selected neurological diseases. Not surprisingly, Alzheimer’s disease won the grant funding category, but this money generated significantly fewer publications per dollar compared to other disease areas such as epilepsy, Parkinson’s Disease, and multiple sclerosis.

Figure 1 – Publications and NIH grants, 2012 – 2015

Figure 2 – Publications generated per $1 million in grant funding

During the subsequent seven years, what have these investments yielded for patients in each of these disease areas?

Table 1 – Research productivity since 2016

| Disease | Clinical Trials1 | Publications2 | Novel Treatments3 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 1218 | 33,700 | 6 |

| Parkinson’s | 1565 | 55,400 | 44 |

| Epilepsy | 715 | 45,800 | 4 |

| Alzheimer’s | 1286 | 80,000 | 2 |

Notes

1. All clinical trials, (ClinicalTrials.gov)

2. All publications (Pubmed)

3. List of Annual Innovative Drug Approvals (US FDA)

4. Includes the approval of Deep Brain Stimulation

Of course, grant funding generates a variety of patient benefits, but let’s face it, new treatments are clearly the most visible and impactful.

The controversial approvals of both highly similar AD drugs raised many questions. The clinical benefit seems modest at best, each has notable side effects, and they command a premium price. Moreover, the nearly $1 billion of annual NIH grant support is only a small fraction of the total research investment in AD, which includes an uncomfortably large number of very expensive, failed clinical trials. Why has so much money has been funneled into AD research for such limited benefit? Clearly the heavy focus on a single disease mechanism, A-beta/amyloid likely squeezed out more attractive alternatives and impeded overall progress. It is certainly worth exploring, as we must learn to avoid these traps. In any case, a look into the status and prospects of alternative mechanisms is warranted. Stay tuned for more on this from Iquant.

Let us know how we can help enhance your research.

We work with scientists, drug discovery professionals, pharmaceutical companies and researchers to create custom reports and precision analytics to fit your project's needs – with more transparency, on tighter timelines, and prices that make sense.