NIH Grant Funding Across CNS Diseases

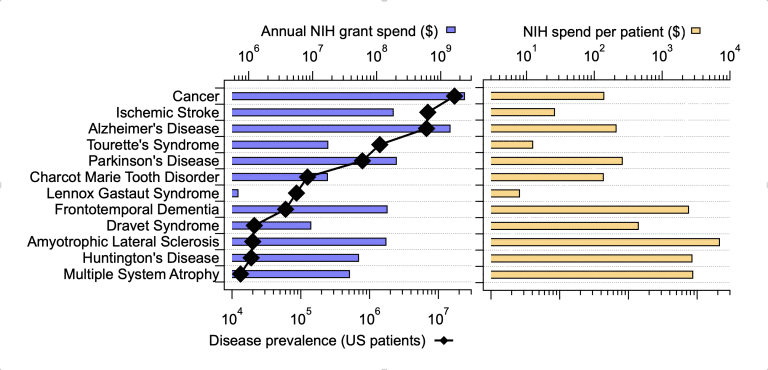

What guides NIH in distributing grants funds across diseases? A mix of medical need, scientific opportunity, and potential societal benefit are likely the primary drivers behind those decisions. However, I wouldn’t be surprised to see influences from patient advocate groups and federal politics creeping into the ultimate distribution of grant funds. We employed the IQuant engine to investigate this issue more deeply, beginning with sheer patient numbers as a rough surrogate for “medical need”. We analyzed the relationship between disease-specific funding levels over the past 5 years and estimates of US disease prevalence from 2022. We looked at a selected set of CNS diseases and compared them to cancer, writ large.

Notes

1. Average annual funding of extramural grants over the past 5 years.

2. Sources: cdc.gov – Cancer Data and Statistics, alz.org Alzheimer’s Data and Statistics, Nature.com Incidence of Parkinson disease in North America, National Library of Medicine – Stroke Epidemiology: Advancing Our Understanding of Disease Mechanism and Therapy, National Library of Medicine – The Epidemiology of Frontotemporal Dementia, Pubmed – The epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Pubmed – The incidence and prevalence of Huntington’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Pubmed – Epidemiology of multiple system atrophy. ESGAP Consortium. European Study Group on Atypical Parkinsonisms, cdc.gov – Data and Statistics on Tourette Syndrome, Medscape – Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease, Pubmed – Incidence of Dravet Syndrome in a US Population, NORD – Dravet Syndrome, National Library of Medicine – Lennox Gastaut Syndrome

At first glance, overall disease-focused grant funding tracked closely with the number of patients suffering from each disease. Note however, that across these diseases prevalence varies widely from around 17,000,000 for cancer to approximately 13,000 for multiple system atrophy. Things get interesting when looking at the NIH spend per patient across diseases. AD research attracts a respectable $213 per patient, well-aligned with the other “big” chronic diseases such as cancer ($140/patient) and Parkinson’s Disease ($262/patient). However, closer inspection of the per-patient spend in rarer diseases raises some questions. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis research comes in at around $7000/patient and Multiple System Atrophy research receives nearly $3000/patient. Other severe, rare diseases such as Lennox Gastaut Syndrome are funded at surprisingly low rate of less than $10 per patient. It’s clear that overall numbers of patients are not a critical factor in distributing NIH grants. This current analysis did not include direct societal cost estimates (we’re working on that), but it is very difficult to argue that the societal cost of 7 million ischemic stroke patients is 200 times lower than that of 8600 ALS patients.

What else might underlie the differences? Of course, the scientific and medical opportunities in each field, while difficult to quantify, are likely quite variable. Again, it seems unlikely that research in Multiple System Atrophy is 10 times more compelling/rigorous/likely-to-succeed than research focused on Lennox Gastaut Syndrome. Another possibility is the relative number of grant applications coming into the system influences the number of funded applications. However, investigators follow the opportunities when proposing projects and causality between NIH funding patterns and numbers of successful grants clearly goes both ways. Notably our analysis, based on key-word searches, may not fully reflect NIH spending patterns and does not include spending by private organization (foundations and industry). Our search only included extramural grants, while NIH also invests in research through other means. We identified funded grants over 5 years based on searching grant titles and abstracts, which could, in theory, skew some results. For example, the differential diagnosis of Multiple System Atrophy and Parkinson’s Disease is challenging and is subject to significant study. Therefore, some of the grants assigned to Multiple System Atrophy may not be directly focused on that disease.

I would like to believe that scientific and clinical considerations are foremost, but it is clear other factors are at play.

– Dr. Todd Verdoorn

Despite these caveats, our analysis raises questions about how NIH distributes its investments across diseases. I would like to believe that scientific and clinical considerations are foremost, but it is clear other factors are at play. Perceived tractability or feasibility might be a prominent consideration, but a case could be made that more difficult areas require more investment, not less. I believe this is an important question and IQuant is actively researching how to incorporate scientific “quality” and “feasibility” into our analyses.

What about politics? Obviously, some patient groups could be more politically active (or politically connected) than others – leading to large funding differences across diseases. A more subtle form of politics could involve the social networks within each disease-specific research community. Could a more connected, interactive community lead to more NIH funding? IQuant continues to investigate measures of biomedical social network strength and influence. Stay tuned for more detailed analyses.

Let us know how we can help enhance your research.

We work with scientists, drug discovery professionals, pharmaceutical companies and researchers to create custom reports and precision analytics to fit your project's needs – with more transparency, on tighter timelines, and prices that make sense.

NIH Grant Funding Across CNS Diseases

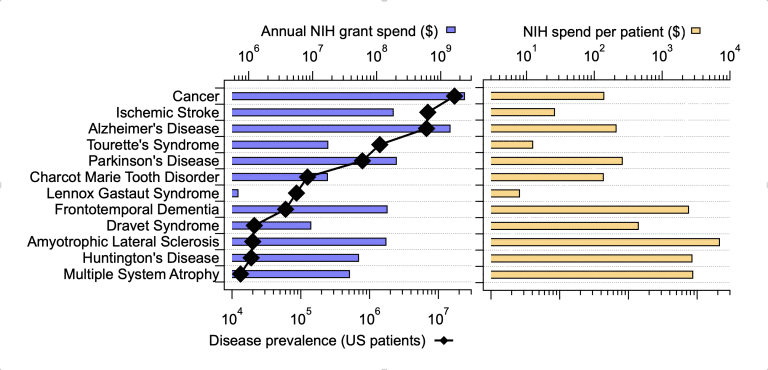

What guides NIH in distributing grants funds across diseases? A mix of medical need, scientific opportunity, and potential societal benefit are likely the primary drivers behind those decisions. However, I wouldn’t be surprised to see influences from patient advocate groups and federal politics creeping into the ultimate distribution of grant funds. We employed the IQuant engine to investigate this issue more deeply, beginning with sheer patient numbers as a rough surrogate for “medical need”. We analyzed the relationship between disease-specific funding levels over the past 5 years and estimates of US disease prevalence from 2022. We looked at a selected set of CNS diseases and compared them to cancer, writ large.

Notes

1. Average annual funding of extramural grants over the past 5 years.

2. Sources: cdc.gov – Cancer Data and Statistics, alz.org Alzheimer’s Data and Statistics, Nature.com Incidence of Parkinson disease in North America, National Library of Medicine – Stroke Epidemiology: Advancing Our Understanding of Disease Mechanism and Therapy, National Library of Medicine – The Epidemiology of Frontotemporal Dementia, Pubmed – The epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Pubmed – The incidence and prevalence of Huntington’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Pubmed – Epidemiology of multiple system atrophy. ESGAP Consortium. European Study Group on Atypical Parkinsonisms, cdc.gov – Data and Statistics on Tourette Syndrome, Medscape – Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease, Pubmed – Incidence of Dravet Syndrome in a US Population, NORD – Dravet Syndrome, National Library of Medicine – Lennox Gastaut Syndrome

At first glance, overall disease-focused grant funding tracked closely with the number of patients suffering from each disease. Note however, that across these diseases prevalence varies widely from around 17,000,000 for cancer to approximately 13,000 for multiple system atrophy. Things get interesting when looking at the NIH spend per patient across diseases. AD research attracts a respectable $213 per patient, well-aligned with the other “big” chronic diseases such as cancer ($140/patient) and Parkinson’s Disease ($262/patient). However, closer inspection of the per-patient spend in rarer diseases raises some questions. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis research comes in at around $7000/patient and Multiple System Atrophy research receives nearly $3000/patient. Other severe, rare diseases such as Lennox Gastaut Syndrome are funded at surprisingly low rate of less than $10 per patient. It’s clear that overall numbers of patients are not a critical factor in distributing NIH grants. This current analysis did not include direct societal cost estimates (we’re working on that), but it is very difficult to argue that the societal cost of 7 million ischemic stroke patients is 200 times lower than that of 8600 ALS patients.

What else might underlie the differences? Of course, the scientific and medical opportunities in each field, while difficult to quantify, are likely quite variable. Again, it seems unlikely that research in Multiple System Atrophy is 10 times more compelling/rigorous/likely-to-succeed than research focused on Lennox Gastaut Syndrome. Another possibility is the relative number of grant applications coming into the system influences the number of funded applications. However, investigators follow the opportunities when proposing projects and causality between NIH funding patterns and numbers of successful grants clearly goes both ways. Notably our analysis, based on key-word searches, may not fully reflect NIH spending patterns and does not include spending by private organization (foundations and industry). Our search only included extramural grants, while NIH also invests in research through other means. We identified funded grants over 5 years based on searching grant titles and abstracts, which could, in theory, skew some results. For example, the differential diagnosis of Multiple System Atrophy and Parkinson’s Disease is challenging and is subject to significant study. Therefore, some of the grants assigned to Multiple System Atrophy may not be directly focused on that disease.

Despite these caveats, our analysis raises questions about how NIH distributes its investments across diseases. I would like to believe that scientific and clinical considerations are foremost, but it is clear other factors are at play. Perceived tractability or feasibility might be a prominent consideration, but a case could be made that more difficult areas require more investment, not less. I believe this is an important question and IQuant is actively researching how to incorporate scientific “quality” and “feasibility” into our analyses.

What about politics? Obviously, some patient groups could be more politically active (or politically connected) than others – leading to large funding differences across diseases. A more subtle form of politics could involve the social networks within each disease-specific research community. Could a more connected, interactive community lead to more NIH funding? IQuant continues to investigate measures of biomedical social network strength and influence. Stay tuned for more detailed analyses.

Let us know how we can help enhance your research.

We work with scientists, drug discovery professionals, pharmaceutical companies and researchers to create custom reports and precision analytics to fit your project's needs – with more transparency, on tighter timelines, and prices that make sense.